Founding of the Nutsspaarbank

It would be going too far to give King William I all the credit for initiating the Nutsspaarbank (Nuts savings bank), but his approval and support were certainly a powerful incentive. The introduction of the Nutsspaarbank was a significant part of a package of initiatives that the sovereign and state introduced in the hope of reducing poverty in the kingdom.

The king who loved saving

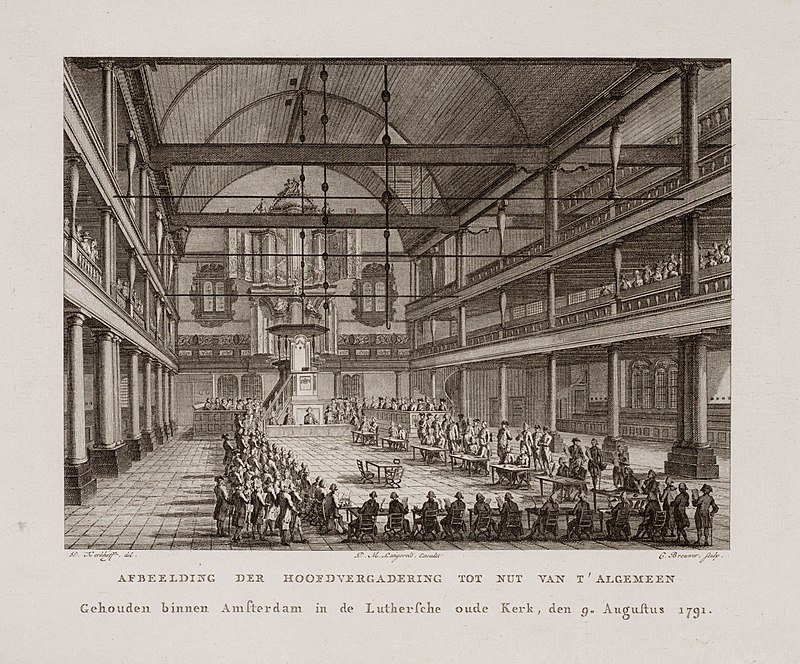

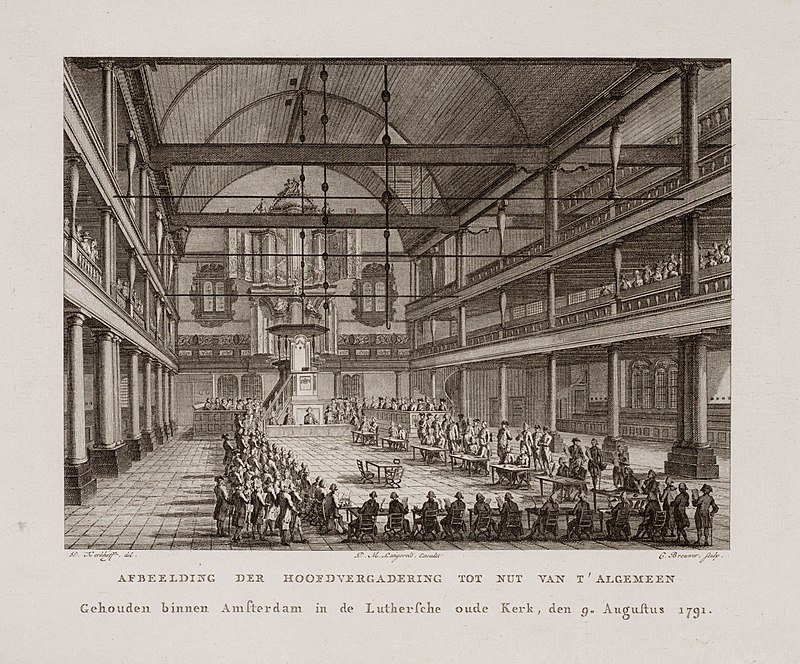

When Prince William Frederick of Orange-Nassau returned to his birthplace in 1813, he found a country sunk in huge national debt and extreme poverty. Two years later, he was crowned King William I and couldn’t wait to help his country get back on its feet. The Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen (Society for Public Welfare) formed an important ally.

The management board of het Nut, as it was known, had regular audiences with the King. This influential society included important representatives of the Dutch elite. They wanted to help the population to develop by providing education and sharing knowledge. In this way, het Nut proved to be a natural ally for the progressive King from the very start.

The management board of het Nut told the King about their experiments with savings banks, and the experience they’d gained in Scotland. The King asked whether het Nut could set up savings banks in all of its branches. Barely six months later, widespread savings banks had been established. The approval and support of the King had been a powerful incentive.

Foundation of het Nut

The Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen was a typical phenomenon in the second half of the 18th century. At the time, many Dutch people were having serious concerns about the country, largely due to the stagnating economy, growing poverty and the government’s inability to turn the tide.

The Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen was founded in 1784, prompted by the Mennonite minister Jan Nieuwenhuyzen from Monnickendam. He wanted to improve the level of knowledge of the average man by providing good education and sharing knowledge by distributing cheap books. Within no time, there were branches right across the country. Anyone could join, regardless of faith or politics.

In 1787, the management board of het Nut moved from the conservative town of Edam to the more liberal Amsterdam, where it remained for almost 200 years. The number of members grew quickly right from the start, but really took off in 1795, at the end of the Dutch Republic. A year later, a branch of het Nut was established in The Hague.

The formation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 was a boost to the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen’s raison d'être. The aim of the organisation was to help the fatherland. But also to encourage people to be more self-sufficient. The King was a powerful ally in this ambition. In fact later historians gave him the nickname ‘Nuts friend’, due to his support for het Nut.

Banking becomes fashionable

It would be going too far to give King William I the credit for initiating the Nutsspaarbank. The local branch of het Nut in the Frisian town Bergum sparked the idea. In those days, people tended to look across the borders for inspiration and that was certainly the case with the savings bank.

The first person to introduce the idea of the savings bank in the Netherlands was Reinhard Scherenberg. As the son of a wealthy Amsterdam family, he tried to tackle poverty in Baarn by opening a carpet factory to provide employment. When this plan fell through, he moved to The Hague and became the King’s advisor on combatting poverty.

In 1817, he wrote an article in the ‘Magazine for poor beings’ about two phenomena: savings banks and help banks. He summarised the findings of a number of Scottish articles and outlined a design for savings banks and help banks in the Netherlands. Scherenberg, and many others with him, saw banks in a very different light. These days, they are institutions that facilitate economic transactions. But back then, they were mainly seen as institutions designed to help prevent poverty. This was the reason for Scherenberg’s article in that particular magazine.

To his mind, savings banks were there intended to take care of money handed over by people who had some to spare and wanted to keep it for their old age or if they became ill. The help banks were intended to lend money to people in financial dire straits. It was an advance that would help them through a difficult period. When they were back on their feet, they would pay it back. It wasn’t about borrowing money to start a shop or a business. The aim of the savings banks was to stop people from spiralling into poverty, not to boost the economy or turn ordinary people into consumers.

The Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen wanted to elevate people out of ignorance, but was aware that the issue of poverty was preventing them from doing this. People who are constantly hungry or fighting for survival simply aren’t interested in improving themselves. The introduction of the Nutsspaarbank was a significant part of a package of initiatives developed by the sovereign and state as a means of reducing poverty in the Kingdom. Once Scherenberg had paved the way, the King called on het Nut to help put the idea of savings banks into practice.

The phenomenon ‘Nutsspaarbank’

The general meeting of 1817 was the first time that the Frisian Nuts branch in Bergum pointed to the beneficial effects of the help banks and savings banks in Scotland. The Frisians asked the management board of Maatschappij how they could set up banks like these in the Netherlands. The board then asked the branches to start some pilots based on this concept. In early 1818, the management board visited the King again, and once again, the sovereign tried to encourage them to establish savings banks. This urgent appeal to the board became a recurring theme in the minutes of the meetings of het Nut.

The encouragement was not only verbal. On 17 May 1818, the Minister for Home Affairs wrote to the management board, stating very firmly that the King had no doubts about the social benefits of savings banks and that he was convinced that het Nut was the appropriate institution to take care of the task.

This started the ball rolling. Every branch of het Nut was invited to set up a savings bank. Some of the branches even started their savings banks before the general regulations had been devised. The Frisian town Workum was the first, with Haarlem, Rotterdam and Dordrecht in hot pursuit. The Hague wasn’t far behind. The King played an active part in all these initiatives by calling on local governments to support the banks. Savings banks sprung up like mushrooms. In 1819, 48 of the 124 branches of het Nut had established one; by 1834, there were 71 Nuts savings banks.

Economic considerations were not the prime concern at the time, and The Hague was no exception. It was all about tackling poverty. The money invested by ordinary savers was not intended to bolster the economy, but to enable them to save and accrue small amounts of interests so that they would see their savings grow (albeit very slowly). The banks were not there to give people credit; mortgages were granted very sparingly. This status quo lasted well into the 20th century. For over 150 years, the Nutsspaarbanks’ raison d’être was to encourage and promote the idea of saving.

The help bank as a step-sister

The second category of charitable banks referred to by Scherenberg, the so-called help banks, were short-lived with het Nut. But the concept of a different form of charitable banking lived on, particularly in The Hague. This is evident in the official foundation of a private help bank in the city in 1818.

The Hague-based help bank was set up by the King’s mother Wilhelmina of Prussia. She donated a lot of money herself. William I made sure that the fund would continue after her death. It was intended to lend money to ordinary people, who had become ill, needed money to pay for their children’s education or to buy tools. The fund also made ‘traditional’ charitable donations. It continued to function as a private help bank until the 1960s.

The number of local help banks started to grow from 1848 onwards; the branch in The Hague opened three years later. Het Nut didn’t play a direct part in this, but the founders were often closely connected with the society. The capital was raised among shareholders, who included well-known names such as Thorbecke and Groen van Prinsterer. In 1867, the help bank in The Hague was the second-largest help bank in the country. It reached its pinnacle in the late 19th century, when it issued a total of 400 to 500 loans. The need for this type of credit gradually receded in the 20th century and the last help bank was officially wound up in the 1950s.

In retrospect, the Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen probably had the right idea in 1818. Saving was a much better option than providing credit. The need for Nutsspaarbanken only started to fade in the second half of the 20th century, when they achieved their original aim of encouraging the Dutch population to save. A result that would have made King William I very proud.